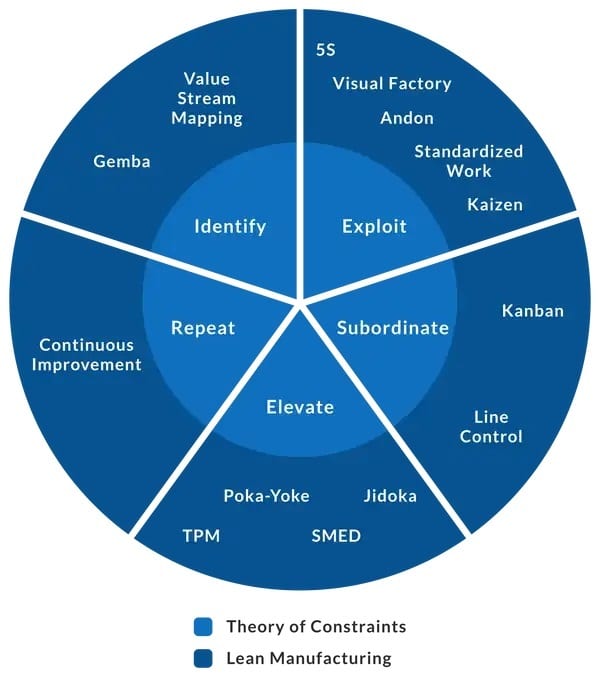

In Part 1 of our Theory of Constraints (TOC) series we looked at how to find (Identify) and exploit the bottleneck in our process. In this post, we are looking at what happens next.

What does it mean to Subordinate to your bottleneck?

Subordinate (as a verb) is defined as:

Treat or regard as of lesser importance than something else. An example is “practical considerations were subordinated to political expediency”

In a Theory of Constraints (TOC) methodology we are interested in subordinating to the bottleneck all of its upstream steps. This means that we make sure the constraint is the most important thing and the throughput of all other steps are viewed as lower priorities. By ensuring that the bottleneck is running at a constant flow, we can be sure there will be a steady output of your product. This constant flow is called the “drumbeat” of your process. We can’t run any other processes faster than our drumbeat.

Why does the bottleneck need to always be running?

The bottleneck is the limiting step in your process

If you look back at part 1 and review the “Exploit” step, you will remember that by optimising the bottleneck you have already maximized its throughput.

You can NOT run it faster or squeeze more efficiency out of it!

So, if you can’t run it faster and you can’t make it more efficiently, this means there is no way to make up for any lost time or lost throughput while it was down.

Putting it simply:

Lost time on the bottleneck = Late product and lost revenue = Poor cash position.

The only exception to this rule is overtime. Most factories are not running 24/7 and if you fall into that group, then you have the option of trying to make up the time with overtime. But as experience Operation Managers will know, overtime is:

- expensive in the short term: paying time and a half

- Expensive in the long term: burn out of employees and sick time increases

- Lowers overall efficiency of workers

So, this option, though appealing, should be a last resort.

How to subordinate?

Subordinating the upstream processes means we might need to relearn some old behaviours. These mistakes are done with the best intention and the behaviours often come from a logical place. However, most often they are not suitable behaviours for small to middle-sized manufacturing companies.

Don’t stop, Won’t stop

The first is the desire to have all machines (or processes) always running. If a particular machining step is not the bottleneck, it will not be required to run all of the time. In fact, to have it running all of the time means you are not using your resources effectively and your cash position will be reduced by driving unneeded inventory up.

Bigger the batch the better

The second is batch size reduction. Many manufacturing companies focus on the efficiencies of a machine or process. This means they will run large batches through the machine to spread the setup time over as many parts as possible. This appears to bring down the time per piece and as a result, appears to reduce the per piece cost. This may be the case on paper, but it can have a huge impact on supply and your cash position.

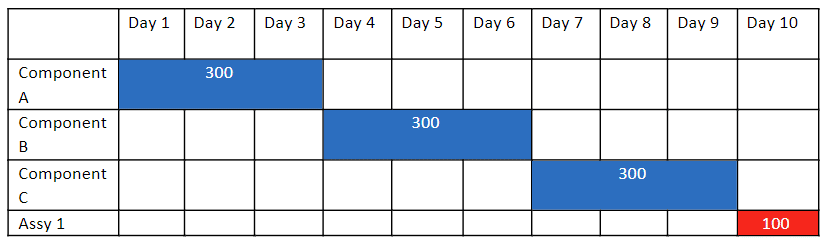

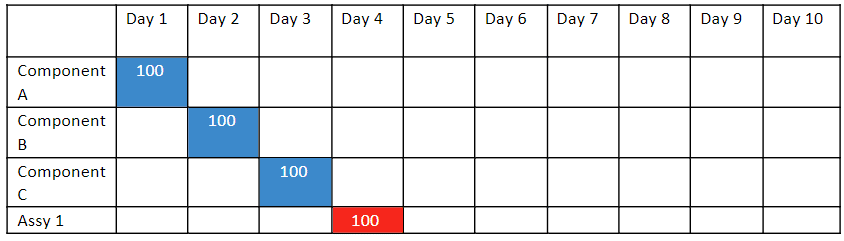

For example, if we revisit our widget factory and a customer orders 50 units of an assembly called ASSY1, which requires components A, B & C.

In Table 1, the company is running large batches of 300’s to ensure the machines are “efficient”. In doing this they are having to run each component for 3 days and they are over-producing each component by 200. The lead time to complete the order is 10 days and ties cash up in inventory.

In Table 2, the company is producing the quantities required for that one order. This means that the correct stock quantiles are produced and it only takes 4 days to complete the order. Resulting in a short cash cycle in the business.

Push through the order

Most of the time when an order hits the shop floor it starts at the beginning of the routing and is “pushed” from one step to the next, irrespective of if that next step is ready for it or not. With a Theory of Constraints methodology, we balance the steps before the bottleneck and “pull” the work into the bottleneck and then pull it into the final dispatch step. This is known as the drum rope buffer or pull system.

In the example above, with our three assembly points, A, B and C, you would only ever pass the assembly from A to B, once B had passed its assembly onto C. This prevents inventory from building up between operations.

Don’t put your constraint on a pedestal, just Elevate it

By Elevating your constraint, we expand its capacity or throughput. In an ideal world, we would bring it up to the required throughput for the whole overall process. In reality, we usually see it being brought up to the next most constraining bottleneck.

Ways to elevate your constraint include

- investment in people. Increased labour or paying to upskill existing workers can help elevate your bottleneck

- Investment in equipment. Automation is a crucial avenue to increasing the capacity of a bottleneck.

- Investment in Design. Can the process be made more efficient by considering Poke Yoke design or other “Design for Manufacturing” techniques?

Continuous improvement

It is imperative that the TOC cycle is continuously reviewed and implemented. The bottleneck may change depending on new or leaving workers. Product mix may play a critical role in the location of the bottleneck. New equipment brought in to elevate a bottleneck may move the bottleneck into a new and unexpected place. By ensuring regular Gemba walks and regular communication with those completing the process occurs, new developments can be identified early and the subsequent exploit, subordinate, and elevate steps can follow close behind.

If you have any questions about the Theory of Constraint or finding, exploiting, subordinating, or elevating your bottleneck, drop us a line!